Why are blanket bogs important?

Originally covering an area of approximately 7,750 km2 (775,000 hectares or 1,915,067 acres), blanket bogs are the most extensive of Ireland’s peatlands. This area accounts for 8% of the world’s blanket bogs. But why are these habitats important?

Blanket bogs are important for a number of different reasons, from social, economic, environmental and cultural perspectives. Bogs store huge amounts of carbon, are reservoirs for drinking water, and provide habitats for unique and endangered wildlife. Explore how bogs are important under the headings below.

Climate

Blanket bogs are a type of peatland. Peatlands only cover 3% of the earth’s surface, but store double the amount of carbon as forests. Undisturbed peatlands accumulate 0.5 tonnes of carbon per hectare per year. It is estimated that a 2 metres deep peatland can store 8,000 tonnes of carbon per hectare. Carbon is captured in peatlands due to the build-up of semi-decayed plant material over time. Plants absorb carbon (carbon sequestration) as they grow on the bog, and due to the absence of microorganism linked to the waterlogged and anaerobic (lack of oxygen) conditions, when they die they don’t fully decompose. The semi-decayed material is compressed to form peat, which holds on to carbon. Sphagnum mosses, a very common bog species, are believed to sequester and hold onto more carbon than any other land plant. Therefore, bogs play a significant role in climate regulation, absorbing carbon from the atmosphere and if intact can store carbon for thousands of years. Irish peatlands, including our blanket bogs, are estimated to store 1085 Mega tonnes (Mt) of carbon, which is 53% of all soil carbon stored on the island of Ireland on just 16% of the land area. Therefore, Irish bogs are one of our most valuable resources in helping tackle climate breakdown.

Nature

While we view blanket bogs as a common habitat in Ireland, globally they are rare. Blanket bog distribution is generally restricted to oceanic areas with high rainfall and includes places such as Norway, Newfoundland (Canada), Japan, Kamchatka Peninsula (Russia), Tierra del Fuego (Chile/Argentina), Falkland Islands, Tasmania (Australia), New Zealand and Britain. Blanket bogs provide a habitat for a range of rare, threatened and in a lot of cases declining species of plants and animals. Although the variety of species found on blanket bogs can be small, many are highly adapted with special survival techniques. See overview of some interesting species profiles…

Sphagnum Moss

As a non-vascular plant (without roots), sphagnum absorbs water and nutrients directly through the surface of the plant. The arrangement of shoots and branches on sphagnum allow easy retention of water. Sphagnum has large empty ‘dead’ cells (hyaline cells) with pores (openings), where water enters the plant. Water is stored in the hyaline cells that make up most of the plant; it can hold over 20 times its own dry weight in water. Sphagnum thrives in wet and acidic conditions, making the bog an ideal habitat. In fact, sphagnum can change the pH of its surrounding environment, creating more acidic conditions to favour its own growing preferences. During the First World War, sphagnum moss was used in wound dressings due to its exceptional absorption abilities, as well as its antiseptic properties.

Sundews, Butterworts and Bladderworts

Sundews, butterworts and bladderworts are insectivorous (insect eating) plants. These bog plants can survive in nutrient poor conditions by supplementing their mineral intake by consuming small insects. Both sundew and butterwort catch insects on their sticky leaves. The small red leaves of the sundew contain up to 200 tentacles, with each having a tentacle with mucus gland at its tip. This gland produces a sticky substance that glistens attracting unsuspecting insect that may think its nectar. Sundews prey on small insects such as midges but larger species such as damselflies have been found to become trapped by multiple leaves simultaneously. On average a sundew can trap up to five insects per month. Ireland has three species of sundew, the most common Round-leaved Sundew (Drosera rotundifolia), Intermediate Sundew (Drosera intermedia) found in the west of Ireland, and Long-leaved Sundew (Drosera anglica), found mostly in bog pools on the bog.

Butterworts also have sticky leaves, which slowly bend over trapping the insect before secreted fluids from the leaf glands slowly digest the prey. Three species of butterwort occur in Ireland, the two larger species are Common Butterwort (Pinguicula vulgaris), and the Large-flowered Butterwort (Pinguicula grandiflora) that can measure up to 8cm across and have violet coloured flowers. The third species is the smaller Pale Butterwort (Pinguicula lusitanica), measuring 1-2cm across with small pale pink flowers.

Unlike sundew and butterwort that are found on the surface of the bog, bladderworts are aquatic, found in pools and water channels in the bog. The name is derived from the bladder-like traps present on the plant stem that are submerged below the water. A passing insect hitting off a trigger hair at the entrance to the bladder activates the trap. A vacuum present inside the bladder sucks the insect inside in less than a second. Digestive fluids are then released from the inner surface of the bladder to help breakdown the prey and absorb the nutrients. Four species of bladderwort are found in Ireland; Common Bladderwort (Utricularia vulgaris), Intermediate Bladderwort (Utricularia intermedia), Southern Bladderwort (Utricularia australis) and Lesser Bladderwort (Utricularia minor).

Dragonflies & Damselflies

Belonging to the Odonata group of insects, there are 24 species of damselfly and dragonfly resident in Ireland. These are the largest insects associated with bogs and are completely dependent on freshwater to complete their life cycle. At least 12 of the Irish species occur on bogs. Odonates are also what’s known as a bio-indicator and their presence can indicate high water quality. Adults lay eggs inside aquatic plant stems or leaves or in the water or wet mud. The early stage of the odonates lifecycle is spent as an aquatic nymph (larva), which feed on small aquatic animals. This stage is by far the longest of the lifecycle, typically lasting one or two year, but ranges from a few months to up to five years for some species. The nymphs then metamorphose (change) and emerge as an adult for the flight period, which lasts only a few months (15-22 weeks), although many individuals will die within a few days of emerging due poor weather conditions or predation.

Golden Plover

The Golden Plover (Pluvialis apricaria) is one of our rarest breeding birds in Ireland and is on Ireland’s Red List of Birds of Conservation Concern (2020-2026) and is also listed on Annex I of the EU Birds Directive. The most recent population census estimate between 134 and 156 breeding pairs. However, these surveys were undertaken between 2002 and 2004 so it’s likely that populations have since declined. Golden Plover breed on blanket bogs in the west and northwest of Ireland. Their diet consists of invertebrates such as craneflies and beetles, as well as plant materials including seeds, grasses and berries, which are available on our bogs. As a ground nesting bird, hatchling camouflage is extremely important to protect the young from predators. Golden Plover chicks match the mosses from the ground flora of their habitat.

Greenland White-fronted Goose

The Greenland White-fronted Goose (Anser albifrons) is one of Europe’s rarest geese species, it being Amber listed in Ireland’s Birds of Conservation Concern (2020-2026), listed on Annex I of the EU Birds Directive and categorised as Endangered under the IUCN’s Red List of Threatened Species. The species name is connected to their summer breeding range in Greenland and the bird’s white forehead. Birds overwinter in Ireland and Scotland and traditionally the species was known as the ‘bog goose’ because bogs were their main feeding grounds, where they consumed the nutritious roots of white-beaked sedge and bog cotton. Unfortunately, many of these bog populations have been displaced due to habitat loss and geese have now been displaced to freshwater marshes and wet grasslands.

Water Reservoir

Blanket bogs are huge reservoirs containing approximately 90% water. Bogs accommodate water bodies (e.g. rivers, lakes, bog pools), regulate water flow and can be a source for high quality drinking water. A properly functioning bog will filter and retain dissolved nutrients, sediments and pollutants present in water, and improve the quality of the water that is eventually released from the bog. Bogs also absorb water like a sponge, regulating water flow by slowing water runoff within river catchments and therefore make the surrounding areas and environment more resilient to floods.

Livelihoods

Our reliance on blanket bogs does not just relate to environmental ecosystem services (e.g. water supply, flood protection, climate breakdown mitigation), but these habitats can support rural communities through incomes from agriculture, tourism and recreation.

The Irish uplands and much of the agricultural lands on the west coast of Ireland are dominated by blanket bogs. Traditionally these lands have been used for rough grazing by cattle and sheep, and it’s important that this practise is managed sustainably. These lands can now attract payments through agri-environment schemes, where farmers are rewarded for maintaining lands in good ecological condition.

Although common in Ireland, internationally blanket bogs are novel, viewed as landscapes with much beauty and intrigue. Many international visitors have never seen a blanket bog before and know very little about them, making them an important asset for tourism and marketing Ireland as a unique tourism destination.

Blanket bogs also provide a variety of outdoor recreational opportunities, that can contribute to the physical and mental wellbeing of Irish society; activities include walking and hiking, climbing, bird and wildlife watching, game shooting, fishing, kayaking and photography. These opportunities can also support sustainable tourism in rural communities.

Heritage

Our bogs and the landscapes in which they are found are of great value culturally. They have provided subject matter for traditions and folklore, inspiration for writers, artists and musicians, as well as preserving artefacts from our ancient past.

The Púca (or Pooka) was a skilful shapeshifter, capable of taking various forms appearing as human, animal or fairy/goblin, or a combination such as human with animal features. The Púca often appeared in rural settings and was associated with using the bogs as passages to either assist or mislead people.

Will-o’-the-wisp refers to distant lights seen over the bog, occurring in both Britain and Ireland. Folktales give accounts of these lights leading people astray over the bog and may have been connected with actual incidents of people going missing in the bogs, and the discovery of bog bodies. A scientific reason for the phenomenon is yet to be established. However, the best explanation is a chemical luminescence or oxidation from decaying organic matter in the bog where gases such as methane are being released, that combusts in the air and produce and blueish-white light. This light then scatters if the air is disturbed, for example if a person approaches the area.

As well as being an excellent carbon store, bogs can store artefacts and landscape features from our ancient past. Beneath the blanket bogs in North Mayo, the Céide Fields is a system of fields, human dwelling and tombs were uncovered and date back to almost 6,000 years ago. Discovered in the 1930s, this Neolithic (Stone Age) monument depicting a farmed landscape is the most extensive of its kind in the world. Anaerobic (no oxygen) conditions have aided the preservation of artefacts, none more remarkable than ‘bog bodies’. Mummified remains complete with facial features, nails, fingerprints and hair have been discovered throughout Europe, having been preserved for thousands of years. Examples from Ireland include the ‘Oldcroghan Man’ from Co. Offaly, Cashel Man from Co. Laois, Gallagh Man from Co. Galway and Baronstown West Man from Co. Kildare. While many of these discoveries have been made in raised bogs, its possible such antiquities are preserved within our blanket bogs. Research into these discoveries have indicated that some were part of ritual and sacrificial deaths and burials. Many objects have been uncovered alongside bog bodies and as indiscriminate items throughout Ireland’s bogs including items of weapons (swords, shields and spearheads), boundary markers, feasting utensils (cups and cauldrons), clothing (cloaks and capes), jewellery and head-dresses, and items connected to milk and corn production (quern stones and ‘bog butter’), amongst many others. All these findings contribute significantly to our understanding of past peoples and their traditions, enriching our heritage and archaeological record in Ireland.

Bogs and the traditions associated with them have been an integral part of works by artists, poets and musicians, both in past times and more recently. The landscapes and seascape of the west of Ireland were of great inspiration for the renowned artist Paul Henry, including works such as ‘An Irish Bog’, ‘A Bog by the Sea’ and ‘The Bog at Evening’. More recent artists such as Barrie Cooke were inspired by nature and the transforming environment; in his work Megaceros Hibernicus, he depicted the now extinct giant Irish Elk (Megaloceros giganteus) a skeleton of which was recovered from the bogs. Many works by the poet Seamus Heaney relate to bogs with a collection of ‘Bog Poems’ that include ‘Bogland’, ‘Bog Queen’ and ‘Belderg’. Music does not escape the sways of the bog either with the very well-known traditional jig music ‘The Geese in the Bog’ played at many a gathering or even modern music ‘Like Real People Do’ by Hozier inspired by bog bodies.

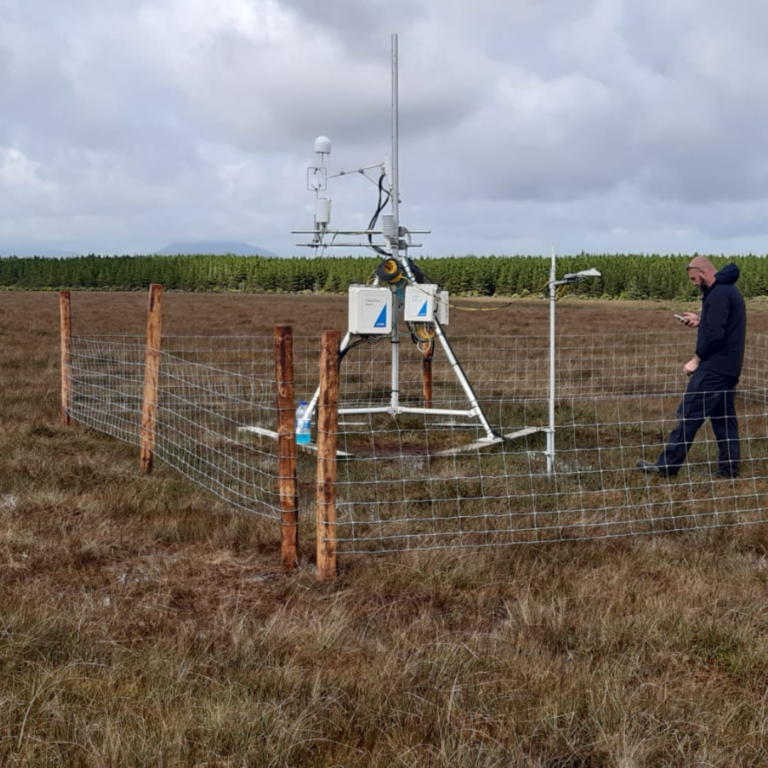

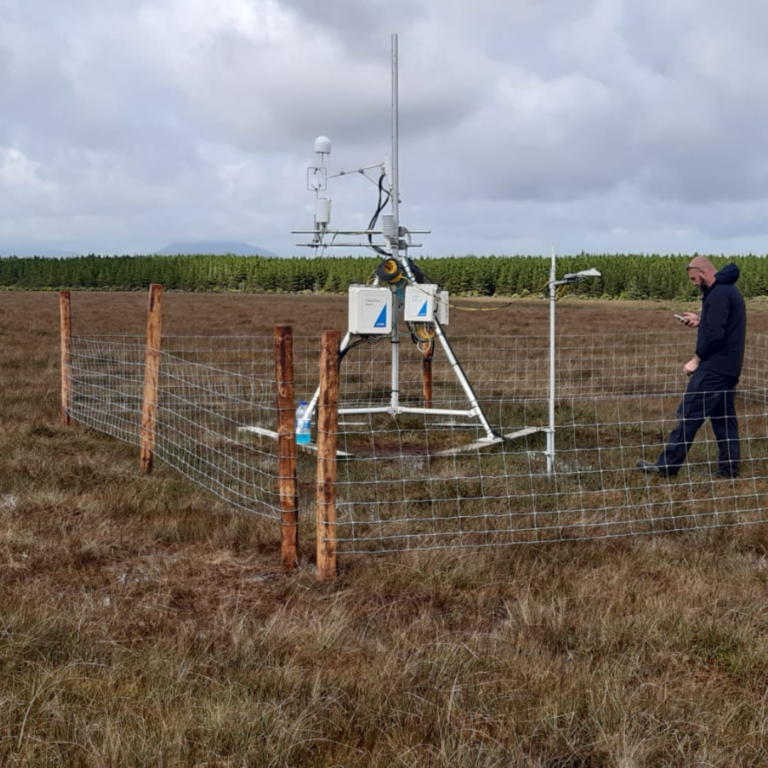

Research & Education

In addition to providing an insight into our past traditions and archaeology, blanket bogs are an important record of our natural heritage and environmental change. As peat accumulates it traps pollen grains from the surrounding vegetation. As bogs started growing 10,000 years ago, preserved pollen at different depths gives us a record over the millennia, allowing scientists to determine regional changes in vegetation over time. Analysis of peat cores can also help document climate change, atmospheric pollution and specific events in history such as the timing of volcanic eruptions. Although widely studied, research continues into many different aspects of Irish bogs. One such project is looking at the potential for bog plants as medicines. Many native bog plants have had traditional cures associated with them such as the treatment of stomach pain or toothache with Tormentil (Potentilla erecta), Sundew (Drosera sp.) used for bronchial complaint or warts, a tonic from Bogbean (Menyanthes trifoliata) for aching joints, coughs, loss of appetite or upset stomach, and heathers being used to treat urinary and diuretic conditions, as well as rheumatism and arthritis. Unlocking Nature’s Pharmacy is a project being undertaken by Trinity College Dublin focusing on identifying potential therapeutic and commercial uses for Irish native bog plants. Discovery and the sustainable production of such medicines could have significant socio-economic benefits to the rural community living in and alongside our blanket bogs.